Return of the Mayflower ,by British Marine Artist Bernard Gribble

On the 6th of April 1917, the United States made a formal declaration of war against Germany. This was quickly followed by the sending of a US destroyer division to Queenstown (now Cobh) Ireland. The Allies were in grave danger of losing the war at this point. The sinking of shipping by submarine and mine had reached unsustainable proportions

Monthly losses were running at 900,000 tons. It was estimated that Britain would have to sue for peace within months, without American aid. The first five destroyers arrived in Cork Harbour, on the south coast of Ireland, on the 4th of May 1917. They were under the command of Commander J.K. Taussig, where they were met by Admiral William D. Sims, Commander of US Naval forces in Europe, and Admiral Lewis Bayley, British Commander Western Approaches.

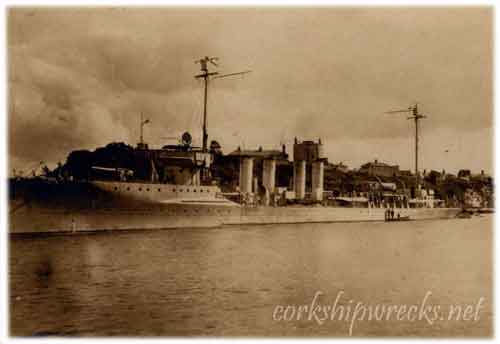

USS Sampson at Haulbowline

Apart from a formal meeting for newsreel footage, ceremonies were kept to a minimum, and within days the destroyers had begun their first patrols.For operational purposes, the United States Naval force at Queenstown came under the operational command of the British Navy. This caused some disquiet among Senior American Naval Commanders and among members of the US House of Congress (the idea of the US Navy being under the command of another state was disquieting to say the least).

Initially there was uncertainty on what was the effective role of the destroyer. The original orders were for roving patrols to engage and destroy enemy submarines, at will. This however was a poor tactic for destroyers, as the almost invisible submarines were spread far and wide. It was the nautical equivalent of searching for a needle in a haystack. Detection devices such as hydrophones were primitive and could only be used when stopped. Radar and Sonar were still years from being invented.

When the destroyers arrived in Ireland they had only single depth charges fitted. Naively It was thought that deck guns would be the main offensive weapon agains the u-boats. Quickly the destroyers had to be retro-fitted with multiple depth charge racks and Thornycroft depth charge launchers It soon became apparent that the best role for the destroyer, was as convoy escort to merchant ships. This gave opportunity for the destroyer to counter-attack any submarine harassing the convoy. It also made these ships invaluable for the saving of life and aiding in salvage efforts

The escorts of the US destroyers and British sloops, would meet incoming convoys up to 300 miles out in the Western Approaches, in all weathers. They would stay with the ships until near their destinations, where they would pick up outgoing convoys.

By the middle of 1917, the convoy system was up and running. The Queenstown destroyers mainly accompanied merchant ships for Liverpool and the south coast ports of England. They also escorted vessels to Northern France. As troop movements to France became more important. A destroyer base was set up in Brest, for troopship operations. This was the larger US base by War’s end. This was a tough brutal duty, with the ever present danger of sudden attack, collision, and mountainous seas to contend with. The Atlantic coast of Ireland is legendary for the ferocity of frequent winter storms. The sea itself , inflicted much damage on ships and men.

USS Prometheus in Cork Harbour

In January 1918. Seven L -Class, US submarines arrived in Cork, via the Azores. Their duties were to be the same as their British counterparts, that of the ‘hunter-killer’, hoping to catch enemy subs in the act of attacking merchant shipping, or recharging batteries on the surface. To avoid confusion with the British L Class submarines, the American boats were designated as AL class for the duration of the war. These submarines were based in Berehaven, West Cork, during 1918

USS AL11 in Bantry Bay

September 1918 saw the arrival in Cork of 36 of the most unusual United States naval craft. These were the Submarine Chasers, a name given to a 110ft wooden launch, powered by gasoline engines. Their officers were mainly peacetime yachtsmen,of the Naval Reserve, who were taken up due to the shortage of trained naval personnel. The powerful Atlantic took its toll on these small craft, which were never designed to cope with winter storms.

US Subchaser SC343 in Cork Harbour

In 1918 there was a general fear that Germany might send out surface raiders against the Atlantic troop transports. For this reason a division of United States Battleships was based in Berehaven under Admiral T.S.Rogers. Their destroyer screen was provided by the ships of the Queenstown Command. These Battleships remained under the direct control of the US Navy, while the rest of the forces were under the day-to-day operational orders of the British ‘Queenstown Command’

USS Oklahoma in Bantry Bay

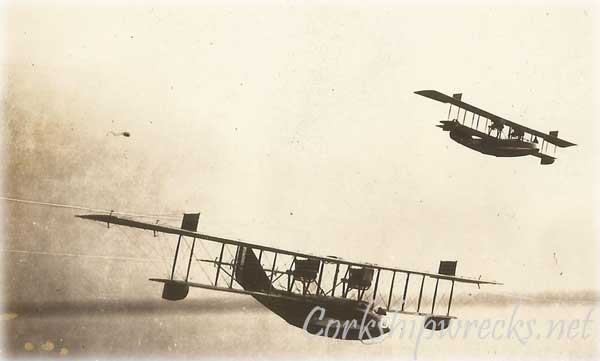

1918 also saw the arrival of the United States Naval Air Service in Ireland. There was a depot set up in Dublin docks.There were flying boat bases established at Lough Foyle, Wexford, Aghada and Whiddy Island. There was also a kite-balloon station at Berehaven.

USNAS Curtis H16 Flying Boat

The only United States 'Q-ship' of World War One, the Santee, was based in Queenstown for her short-lived career.

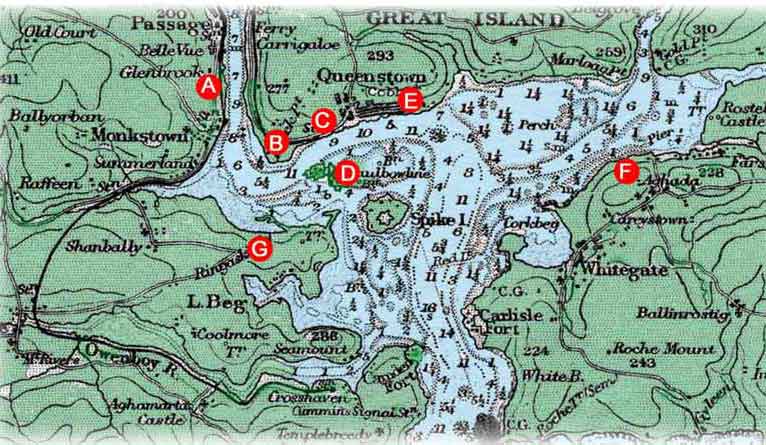

United States Navy facilities in Cork Harbour, 1917 to 1919.

A. Subchaser Base and Barracks, Glenbrook, Passage West.

B. Base Hospital No 4, Whitepoint, Queenstown.

C. US Naval Stores, Queenstown.

D. Torpedo Repair Station and Stores, Haulbowline Island

E. Enlisted Servicemens Club, Bath House Quay,Queenstown..

F. United States Naval Air Service Base, Aghada.

G. Training Classrooms and barracks, Ballybricken House, Ringaskiddy.

By the end of World War One, more than 18,650 ships and two million US troops had been safely escorted through the War Zone. There were a number of tragic losses among personnel serving in the Queenstown Command, with the influenza epidemic of winter 1918 providing more casualties. Base Hospital No 4, was set up in Whitepoint, just opposite Haulbowline.

Base hospital Number 4, Whitepoint

The arrival of vast quantities of United States servicemen in Cork had great social implications. They were far better paid than the British servicemen, and infinitely wealthier than most local men. Tensions quickly rose as local girls were attracted to these exotic arrivals, with access to all the luxuries which were scarce locally. The co-operation and fraternisation between both navies, much lauded in history books, appears to have occurred only between officers. There was marked hostility between the enlisted ranks of both countries, but this was defused by both sides having their own favoured pubs ashore.

US and British Servicemen at a concert

Reports added that there was very little interaction (and consequent trouble) between them. The US personnel also had their own Servicemens’ Club, built on Bath House Quay, at the eastern end of Queenstown. The British naval personnel had the use of the YMCA buildings on Promenade Quay, beside the White Star building.

sailors pose with German mine, (probably one of those recovered from UC42 or UC44 )

The Americans, both officers and men, were appalled by the the abject poverty of parts of Cork and Queenstown. They quickly became targets of beggars and street children, and found the constant attention overwhelming. Letters appeared in the local newspapers complaining about this. Replies were instantly forthcoming from Cork correspondents who implied that it was the Americans’ own fault, for showing off their wealth, and their practice of tipping, almost unheard of in Ireland, and seen in some quarters as vulgar and demeaning.

There were some incidents, and in September 1917, there was a reported riot on King Street, Cork (now McCurtain Street), between US sailors and British soldiers. In January 1919, there was a melee between US Sailors and British soldiers on board the Rosslare express train from Cork. When the train arrived in Waterford, most of the windows were broken, and a number of the American sailors were injured. One was missing, and it turned out had either been thrown off, or fallen from the train. He was found in Dungarvan, , none the worse for wear.

A Destroyer Crew

The divisions between sections of the local population and the US Navy ran a lot deeper. There were a number of attacks on enlisted men, and running battles on the streets of Cork City, between locals and naval personnel.These events culminated in the death of a local man, Fred Plummer, after a brawl. Newspaper reports were blaming the trouble on ‘Sinn Fein’ elements, but the reasons were probably a lot baser. One sermon from the pulpit of Cobh Cathedral inflamed the situation, blaming the lax morals of the young sailors. . When officers found servicemen on board the USS Melville fashioning knuckle-dusters and other weapons, things came to a head

Bluejackets ashore

Cork City became off-limits to enlisted men for the duration. A deputation was sent from Cork asking the authorities to reverse the decision, but to no avail. They were asked by Admiral Bayley, if they could guarantee the safety of US Bluejackets in the city, and of course they couldn’t.

There was clearly some hostility towards the US Navy from part of the Irish population. This was barely a year after the failed 1916 Irish Rising, and subsequent execution of some of its leaders. There were those who could not understand why Americans, many of whom were of Irish descent, were fighting to keep the status quo of British rule in Ireland.

It was said that “If America was fighting for the freedom of small nations – why was it preventing one small nation from gaining it’s freedom”? It must be remembered however, that there were 400,000 Irishmen in the British Forces in World War One. Between 40 to 50,000 Irish soldiers and sailors lost their lives. Ireland's history is complex, and reasons for Irishmen serving in the British forces ranged from seeking adventure, to loyalism, family tradition, to promises of Home Rule. If you were the youngest son of smallholder in rural Ireland, the military was probably one of the only career paths open

The vast majority of Cork people seemed to deal with the appearance of all these young Americans with a sense of pragmatism. Friendships were formed, dances were held, romances blossomed , and marriages came. The phenomenon of the ‘War Bride’ did not just appear in World War Two. The train from Cork to Queenstown became known among the sailors as the 'Dove Train', carrying many young Cork girls eager to step out with a 'Yank'. (Among cynics it was known as the ‘Soiled Dove Train’)

There was a darker side to this interaction. As a port town, with a naval base and dockyard, there had always been prostitution in Queenstown, usually concentrated in the east of the town - in the ironically named 'Holy Ground'. As early as July 1917, Queen Street, in the east end of Queenstown was ruled as 'out of bounds' to American servicemen. With such a large potential clientelle, prostitutes now travelled to Queenstown in large numbers, not only from Cork, but Dublin and even London.

The attraction of the American sailors and their money became a headache for the RIC in Queenstown. 26 women were convicted in Queenstown in 1918 of 'committing acts contrary to public decency on any street' , It was more common however, to convict the women on the more ambiguous charge of 'vagrancy'. Under the Defence of the Realm regulations, they were served with notices barring them from residing in the Great Island area. In nine cases the order was disobeyed, and the women received sentences of three months imprisonment.

On the 18th of March, 1918. There was a riot at Cork Railway Station. A crowd estimated at 300 men and women, gathered and attacked the women travelling on the train to Queenstown. They were beaten with sticks, stoned and had items of clothing pulled off. The station master telephoned the police and the crowd were dispersed with baton charges.. There was a repeat the next night, but a large force of police under District Inspector Swanzey (later killed by the IRA), baton charged the crowd and dispersed them. There does not seem to be any evidence that this incident was organised by the Irish Volunteers. It doesn't appear in any of the accounts of their actions.

Documentary evidence for local attitudes to the presence of US naval personnel has increased in recent years, with the posting online of the Irish Bureau of Military History collection.

http://www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/about.htmlThese accounts reflect the views and recollections of some of the the participants in The War of Independence in Ireland. They are however far from complete, representing a partisan view, and they largely have virtually no accounts from those who took the Anti-Treaty side, in Ireland's Civil War. The most comprehensive of these is recounted by Michael V O'Donoghue, Engineer Cork 1 Brigade IRA, 1921; President GAA, 1952 - 1955. This account - which must be viewed in the context of peoples social attitudes and norms in those times, gives a remarkable view of the personnel of the lower decks of the US Navy, and their attitude to Ireland and the Irish people.

www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1741%20PART%202.pdfA More brusque and less complimentary account of the US sailors is given in the record of Seamus Fitzgerald, later member of the Dail and Seanad.

www.bureauofmilitaryhistory.ie/reels/bmh/BMH.WS1737.pdfWith the arrival of the Armistice, in November 1918, it was time to begin the withdrawal of the United States Navy from Cork. In March 1919 Admiral Sims returned to the United States, on board the Mauretania. Rear-Admiral H.S. Knapp, succeeded him, in command of Naval Forces in Europe

By May 1919, most of the Naval Hospital huts had been dismantled, apart from those taken over by British forces. The Aghada base buildings were being auctioned off. The stores on the seafront were to go. All the ships had departed, apart from Corsair , the yacht of the billionaire J.P. Morgan, which had taken over from USS Melville as the base for the Officer Commanding. By June even the Corsair was gone.

Over one hundred and ninety US naval personnel lost their lives while based in Ireland. Casualty figures given here , largely only include deaths up to the Armistice, in November 1918. There was a US presence in Ireland until at least July 1919, but casualty lists are difficult to determine for this period. Some remains were interred in Ireland, while others were immediately shipped to the USA.

In November, 1919. The US Naval vessel Yankton (a steam yacht which had been used as a patrol vessel, in France), visited Queenstown. Under the direction of Dr Clarke Andrew, the remains of US personnel interred in Clonmel Old Graveyard, were exhumed. These bodies were then transported back to the USA for re-burial. In all, the remains of thirty two US sailors were repatriated to the United States from Ireland in 1919.

Irish history moved on, through the bitter War of Independence from Britain, the even more bitter Irish Civil War, and the foundation of the Irish State. The US Naval presence in Cork became a footnote in history, as the generation passed on.

The US Naval stores buildings at Deepwater Quay were finally demolished and sold off in 1921. One portion of the stores was taken over by Cork Harbour Commissioners and survived until the 1950's as a customs clearance shed for liner passengers.

SOURCES

There have been a number of publications detailing the history of Queenstown (Cobh) during World War One. The standard reference works are those those listed below

Danger Zone. The story of the Queenstown Command.

By E.Keeble Chatterton

Little, Brown and Co, Boston 1934

(copy available in Cork City Library – local history section top floor)

The Victory at Sea. By Rear-Admiral William Sowden Sims, Doubleday, Page and Company, New York, 1921.

Simsadus London, The American Navy in Europe.

By John Langdon Leighton.

Henry Holt & Co, New York, 1921.

Available to download here

Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy

For the Fiscal Year, 1918

Available to download here

Officers and Enlisted Men of the US Navy who died during WW1

Available to download here

Bayley’s Navy,

by Vice Admiral Walter.S.Delany (Rtd)

Available to download here

American Participation in the Great War,

by Captain Dudley W.Knox.

Available to download here

Naval Aviation in WW1,

by Adrian O. Van Wyen.

Available to download here

For Operational Records Various files from the Public Records Office,of the United Kingdom, Kew are invaluable, especially records of ADM137, which were files bound for the official history of WW1 Naval Operations. None of these records are digitised yet, and can only be accessed by visiting the British Public Records Office, Kew, near London.

www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

For photographs of the Queenstown Command, the following websites have many photographs available to download free of charge. Most of the aforementioned publications also have photographic illustrations.

US Naval History and Heritage Command website

www.history.navy.mil

United States National Archives Website

www.archives.gov/

The British Imperial War Museum

www.iwm.org.uk/research

This site contains many photographs of US and British Naval operations in Ireland. Importantly, it also has a number of copies of unique newsreel footage. These can be played on the site.